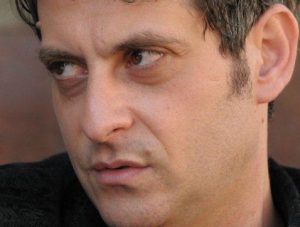

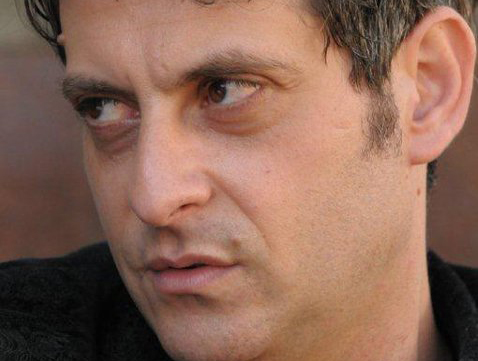

Raji Bathish is a writer, screenplay writer, cultural researcher and activist born in Nazareth 1970. He writes in Arabic, and his texts and articles have been published all around the Arab world and Israel-Palestine. Raji has authored nine books, the most popular among them is “A Room in Tel-Aviv”, which was published by the Arab institute for Studies and Research in Beirut 2007.

Raji Bathish is a writer, screenplay writer, cultural researcher and activist born in Nazareth 1970. He writes in Arabic, and his texts and articles have been published all around the Arab world and Israel-Palestine. Raji has authored nine books, the most popular among them is “A Room in Tel-Aviv”, which was published by the Arab institute for Studies and Research in Beirut 2007.

Raj is known for his controversial style, where he approaches the themes of sexual desire and lust with a modern and cosmopolitan language. He is well versed in literary theory and queer theory, and has been one of the pioneers of queer literature in Palestine and the Arab World. Laghoo is pleased to publish this interview with Raji Bathish, where we asked him how he deals with the controversial in his writings, and how he addresses taboos.

1. Do you think writing about taboos is a necessary thing?

I don’t know what taboos exactly mean here. In general, we, Arab writers, imagine in our pan-arab nationalistic thoughts, that our taboos are one monolithic entity. On the contrary, I often find sharp differences in taboos between one neighbourhood and another, between one street and another in the same city. I can’t pile up a group of taboos and talk about them. I think what we need to do is to shift and broaden the boundaries of creative writing. The boundaries of language need to be shifted, since language is the primary form of knowledge, and the primary raw material that any writer utilizes. It is necessary to liberate language from the inside, and not by requesting approvals from society or government. Writers in the Arab World escape from confronting the issue by talking about barriers imposed by society, religion, and norms. The problem is that these writers are not free in the way they express themselves, therefore they are not liberated conceptually. Our writers are too polite.

2. Is there a specific controversial subject you prefer to write about

Generally speaking, I do not write anything unless it is controversial. My writing has to shake the readers and uncover hidden stories. I like to dig where embarrassment is located … creative writing has to be controversial, otherwise it would not be needed. In that regard, I am always drawn to writing erotic and pornographic fiction, which starts from lust and sexual desire and ends up in psychoanalyzing the miserable human condition.

3. In your opinion, is there a controversial subject one should not or must not express or write about?

Perhaps you are looking for an answer, but I will disappoint you and not give it to you … I am speaking on my behalf here, and not representing others. Honestly, I do not like to write about religions, their necessity, their history, etc … not out of fear .. simply, I don’t care about the subject. I have never gone deep into it, and I have never followed the trend and fixation on Canaanite mythology that dominated Palestine in the nineties, despite the fact that I have learned my Arabic diction from the Catholic Church and its prayers translated to Arabic. I have never gone deep into it. It didn’t matter much to me. It seemed too naive and too peaceful. Since the beginning, I have focused on writing about desire and flesh in the broad sense.

4. Do you think about the reader or the audience when you are writing?

i am crazy about readers. I do not write for myself, and I am not one of those who keep their work in the drawer out of fear of reactions. The impulse to read, and matters such as fame and being distinguished keep me moving, and I am not shy about it. I am telling you, since I was 17 years old, I have never hidden or damaged any text. I have published all what I have written either in magazines or in books. Concerning the writing process itself, when I write a new text I imagine a certain reader, he/she is a mix of people whom I know virtually or in real life. Following each sentence or paragraph, I watch the reactions of this imagined reader, which are not actual reactions of course, but reflections of the sentence or paragraph on the reader’s face. It’s a complex process which is not easily understood.

5. How do you balance the real and the metaphorical in your writing, and

I don’t. For me, they are connected and intertwined, partially and fully sometimes. For the last few years, I have lived by myself where I have interacted with people outside. At home, inside, is where there is no difference between the real and the imaginary, the alive and the dead, the literal and the metaphorical. At home, things and physical elements take other meanings, perhaps metaphorical. The colours, the smells, the pictures, and the relationships with the absentees. All of this happens in my head, on my own, and I do not share it with anybody. This is reflected in my recent work. I don’t remember the last time I had written a political article or a “rational” sociological article. Often I am asked to contribute to a book or a feature about some subject. I try my best to avoid declaring that overlap, and it is a difficult mission, no doubt.

6. Do you feel that sometimes you betray your idea because of the indirect writing?

Not at all. I write my direct thoughts on Facebook, which is an effective and fast tool, although there were doubts about it in the beginning. Sometimes, I miss the weekly column, but in our crazy region, how would you guarantee what will happen in a week? The cultural opinion type of article has turned into spoiled commodity. Issues now are reflected on Facebook walls not in essays and articles.

7. In terms of priority in cultural influence, how do you classify the following controversial themes: religion, politics, and woman/gender?

I believe that the gender issue is the most important since it carries layers of controversial matters. Social and cultural freedom will not evolve without breaking the binary system that controls us, most importantly, the man/woman and the master/slave binaries. All religious, political, and military paradigms are patriarchal paradigms that cannot be deconstructed without reproducing social roles and hierarchical relationships amongst gender types and identities. Accordingly, changing the role of the marginal and moving it to the centre. The queer movements (as opposed to the neoliberal gay movements) holds this spirit, although it is often trapped into the euro-american centrism.

8. Have you been subject to criticism or terrorism because you tackled controversial topics in your works?

Probably .. I don’t know .. it has never happened in front of me. Probably indirectly or through dirty commentaries from online readers. Anyways, my assumed readers do not live in my daily-life sphere, therefore I am not an easy target for those, whoever or whatever they are. Since we are talking about this, in 2007, I published a poster, with some friends, in 2007, where we poked fun at selling tickets for a poetry reading by Mahmoud Darwish in Haifa. I was threatened to be beaten up by one of the organizers if I showed up to the event. Isn’t Mahmoud Darwish, whom I love his poetry, one of the taboos.

9. Can the controversial and the sacred possibly coexist in the Arab world?

I am one of the romantics who believed in the Arab Spring. In my opinion, the Arab Spring has not turned into fall or winter … the revolutions did not happen to remove oppressive regimes and replace them with regimes that are less oppressive … I still believe that the revolution has occurred although at a slow pace within the consciousness, therefore there is no return to the past. The controversial is not the same as the years prior to 2011 and the sacred is not the same as the years prior to 2011, there is chaos where the controversial and the sacred coexist, and there will be somebody who will keep trying to violate the sacred every single day. There will be somebody who will try to suppress whoever intends to rebel. There will be societies that will protect the rebellious and there will be others who would cast him as an outside and call him an infidel. That would not come only from religious backgrounds, but also from nationalistic motives. This will keep happening again and again.

Interviewed and translated from Arabic by: Ashraf Zaghal

The Writer and the Taboo: with Naser Al Zafiri

The Writer and the Taboo: with Liwaa Yazji

The Writer and the Taboo: with Karl Sharro