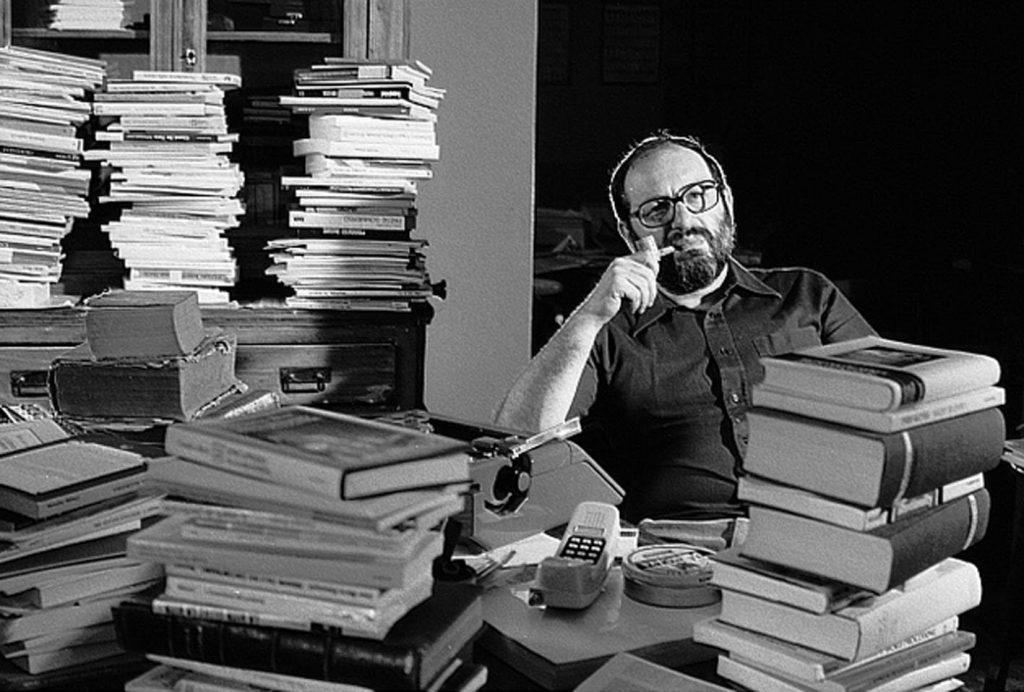

Naser Al Zafiri is an Arab-Canadian writer and novelist based in Ottawa. He has written five novels and two collections of short stories. He has published numerous articles in Arab literary magazines and newspapers. In his work, Naser tackles controversial themes such as nationalism, power structure, and gender issues in the Arab World.

In this interview, he eloquently elaborates on addressing taboos in his novels and articles.

1. Do you think that writing about taboos is really necessary?

It is necessary to break religious and social taboos so that society can change and break out of the stagnation it is experiencing under the weight of the discourse of sacredness rejected by scientific progress in all aspects of scientific and human life. Writing about taboos is not futile or trivial violation, nor is it a provocation, of collective sentiments; it is an effort that can result in shifting well-ingrained attitudes in people’s minds. The opposition to fixed values and the movements for change have to bring different convictions accepted by society. This is what happened in most societies throughout the world during their transition from one era to another, and our Arab societies are not an exception.

2. Is there a specific controversial subject you prefer to write about?

The political and social conditions I experienced in Kuwait as well as the impact of the political power on me that led me to choose exile over staying in my homeland have resulted in making power the focus of my work. Power and its relationship to the individual—the individual’s refusal to surrender or comply with power structures; the power’s opposition to the individual’s existence and their livelihood, combating their personal relations and interference in all the details of his/her daily life—this is what I tried to write about.

3. Is there a controversial topic that you think should not be tackled, and that you must not write about or express?

I do not think we should refrain from writing about any subject. Some may believe that the time is not appropriate to discuss some thorny issues, but I do not agree with this view. We have to write about everything that matters to humans.

4. Do you think about the reader or the audience when you write?

I only think about the text and the extent of my conviction in it. Within every writer there is a censor and a critic that can determine the level of their work, and for a writer to be successful, they have to successfully critique themselves first and measure their writing on the same level of their reading. They have to keep aspiring for work with which they identify and which they admire; they should not compromise even if this means that they have to write off more than one text.

5. Would you support a specific form of censorship?

I cannot accept censorship in any form or shape, but I am with resorting to just law in the event of a damage incurred to a person or an entity by dishonest writing. This just law is a demand that has yet to be met in the Arab world, and it is in the hands of the power that established censorship and is supervising it.

6. How do you balance between the real and the metaphorical in your writing?

Everything we write about is real but not necessarily realistic; even pure imagination is a reality that has been embodied in a fictional text. We have not necessarily encountered it in real life, but it is alive as a textual body experienced mentally. I often resort to metaphor, not as a deviation from truth but to give this truth a chance to be validated.

7. Do you feel that you betray your idea sometimes because of indirect writing?

I have not written in an indirect way, and I do not need symbols in my writing; nor do I betray the idea. All my work is direct and taps in the heart of the idea that I examine. It is important that literariness be part of the novelistic writing; the idea is always clear.

8. In terms of priority in cultural influence, how do you classify the following controversial themes: religion, politics, and woman/gender?

There is a famous saying, “Oh my God, the queen is pregnant!” It is a saying that people avoid in order not to confront the religious, political, and patriarchal power structures in immutable societies. The religious impact is the most significant culturally, as the conflict appears to be with God rather than with the human element that has replaced God on earth. The Arab ruler has associated himself with God, so that a conflict with him is a religious offense that leads to the accusation of infidelity. The fear of woman’s freedom and ability to influence her surrounding have been linked to religious concepts, restricting her to these same concepts. We have to change the religious concepts in order to be able to disentangle these problematic relations.

9. Have you been subject to criticism or terrorism before because of addressing controversial topics in your works?

Honestly, I never faced any personal harassment for my writings when I was a university student until I left Kuwait. My first collection was banned during the disruption of the political and parliamentary life in Kuwait in 1987; I published it three years later. My novel Kaliska was banned two years ago, but personally I have never inquired about my writing.

10. Can the controversial and the sacred coexist in the Arab world?

I firmly believe that the Arab world is coming to a major change that will uproot the sacred idea enshrined in humans as substitutes for God and agents interpreting His teachings. There will be a great cultural movement leading society to new experiences without abandoning its cultural identity or great history, the same history that has been disfigured by the contemporary religious movements.

Translated by : Ghada Mourad

Interviewed by: Ashraf Zaghal

The Writer and the Taboo: with Raji Bathish

The Writer and the Taboo: with Liwaa Yazji

The Writer and the Taboo: with Karl Sharro