“When one leaves the hurry and roar of lower Broadway and walks southward through narrow Washington-st., the average New-Yorker of Caucasian descent might easily believe he was in the Orient. A block to the east roar the trains of the elevated. A little further eastward are the rushing throngs of Broadway. In the midst of all this tumult and confusion is situated the quiet village of Ahl-esh-Shemal.”

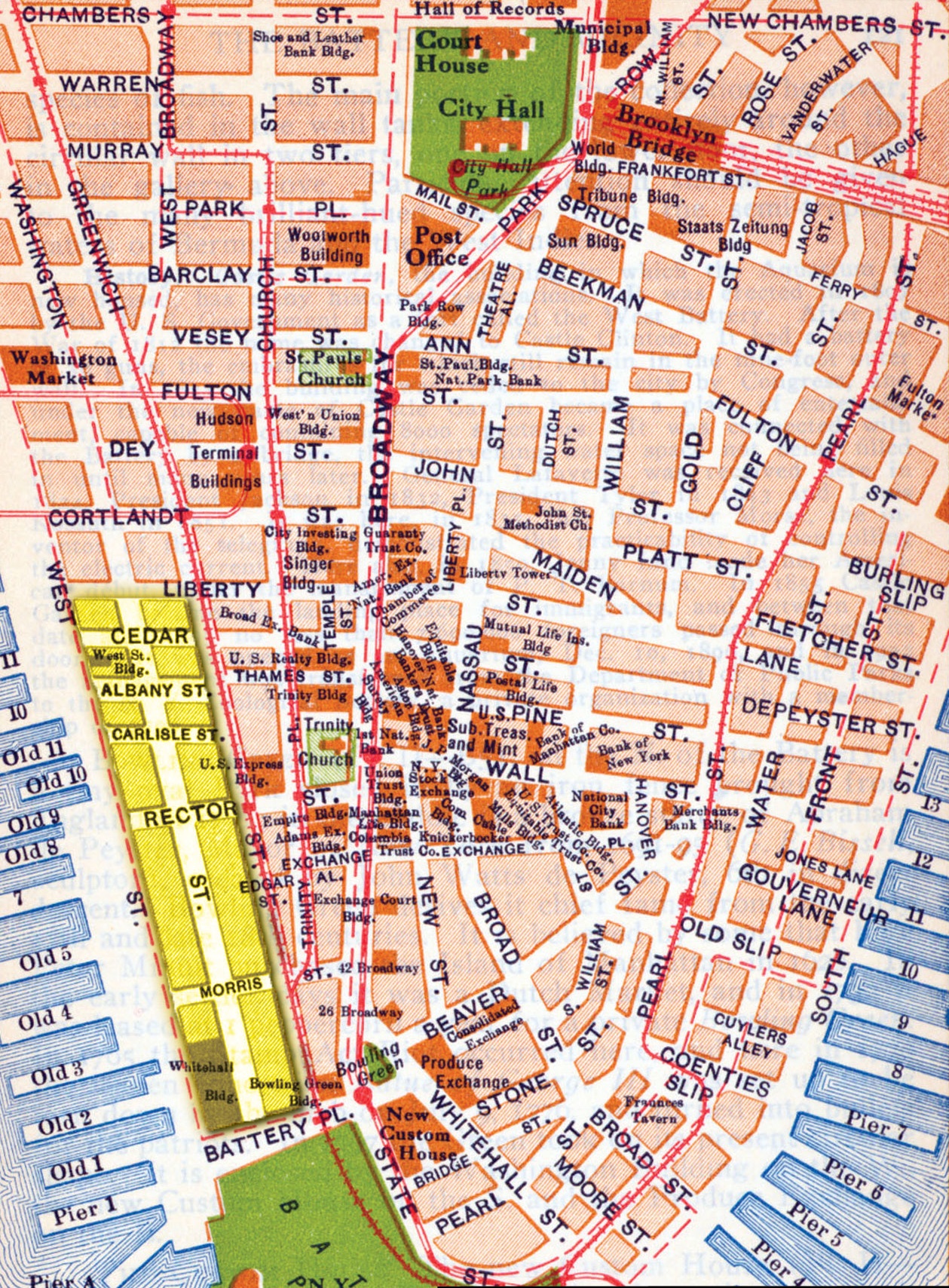

And so, in 1903, the New-York Tribune endeavors to take its readers into Little Syria. Concentrated on Rector and Washington Streets in the lower parts of Manhattan, Little Syria in 1895 was home to an estimated three-thousand residents from modern-day Syria and Lebanon (nearly all Middle Eastern New Yorkers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries would be referred to as Syrian or Arab, regardless of religion), most of whom had fled persecution under increasingly harsh Ottoman rule. Missionaries, dispatched to the Holy Lands to spread the Christian gospel, told tales of a city made of opportunity, ready and waiting to receive immigrants dedicated to hard work and moral living.

And so, in 1903, the New-York Tribune endeavors to take its readers into Little Syria. Concentrated on Rector and Washington Streets in the lower parts of Manhattan, Little Syria in 1895 was home to an estimated three-thousand residents from modern-day Syria and Lebanon (nearly all Middle Eastern New Yorkers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries would be referred to as Syrian or Arab, regardless of religion), most of whom had fled persecution under increasingly harsh Ottoman rule. Missionaries, dispatched to the Holy Lands to spread the Christian gospel, told tales of a city made of opportunity, ready and waiting to receive immigrants dedicated to hard work and moral living.

“Slumming,”, in which those who could afford to avoid slums toured them in search of titillation, happened in virtually every ethnic enclave south of Fourteenth Street. Descriptions of Italian filth and Irish degradation filled the city’s more lurid papers. Little Syria, or the “Syrian Ghetto,” was, the New-York Tribune warned, not to be romanticized any more than the opium dens of Chinatown or the dive bars of Mulberry Street:

“There is nothing gorgeously romantic about this tousled, unwashed section of New York. The entire City of New York cannot show anything more villainously filthy than the old tenements on the west side near the foot of Washington Street, and the dens on their lower floors. Here hags and heldames gather, wretched old men and great families of dirty children, besides fat matrons and workmen, who not think it worth the while to wash off the grime of toll.”

In New York State, a tenement is defined as any building housing three or more separate families. Legally, 109 Washington Street, Little Syria’s largest tenement building, was no different from The Dakota, a hulking 1884 structure at 71st and Central Park West that, by the 1890s had come to symbolize everything that was glorious about this new urban life.

To even whisper the word tenement to a fine gentleman of the nineteenth century would be to induce shudders of revulsion based on descriptions like the one above, or, depending on the fellow in question, stirring of the kind of lust reserved for that which is other. Every account of Little Syria written by an outsider makes reference to the neighborhood’s women—and their looks. Some are favorable—the Times, in 1903, noted that one might hope to meet “a girl whose ears are weighted with heavy gold hoops, and whose apparel savors strongly of the East.” Teenaged girls of the Syrian Quarter, the paper continued, were especially comely.

But where some men see beauty others see its opposite—in the Little Syria of 1899, a psuedo-travelogue published by the New-York Sun warned, “hags there are in great plenty, some dozens of stout matrons, but so far as street life goes the Eve of Syria, the Leila, best beloved of Ali, is not there.” In general, the Times agreed—on Washington Street, ”men and women alike, have little that is attractive about them.”

But where some men see beauty others see its opposite—in the Little Syria of 1899, a psuedo-travelogue published by the New-York Sun warned, “hags there are in great plenty, some dozens of stout matrons, but so far as street life goes the Eve of Syria, the Leila, best beloved of Ali, is not there.” In general, the Times agreed—on Washington Street, ”men and women alike, have little that is attractive about them.”

Immigrant women under the age of thirty (the country of origin mattered little, unless one had an especial dislike or predilection for an accent) were (and, quite frankly, still are) a playground to men with the money and the privilege to treat them as such. Brothels lining the Bowery and the streets off Broadway (and, by the early 1900s, the streets surrounding Madison Square) were filled with the daughters of Ireland and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and so, upon visiting the Syrian Quarter, reporters took great pains to note that the women of that neighborhood were less accessible than some might have hoped:

“In its bounds there are, indeed, a number of pretty girls, prettier, one is tempted to assert, than those of any other foreign colony of New York could bring forth. But—and here is another point that distinguishes the Syrians from all the other foreigners of the city, these public dancing maidens—keep very closely, day and evening, to their homes.”

One did not, to put it in the crudest terms of the Gilded Age, go whoring in Little Syria.

If Washington and Rector Streets had no dives, no houses of assignation to offer amusement to the city’s elite, what reason was there to make the trip? Unlike Little Italy (unsafe; dirty) or the Jewish Lower East Side (confusing; crowded), the Syrian Quarter offered New Yorkers a chance to interact with (and take from) an immigrant culture they found “queer, but civilized.” Politeness, according to the Sun, was the chief currency of the streets:

“The first thing that strikes the visitor to the Syrian quarter is the uniform politeness of then men. They never push or jostle, and when the narrow sidewalk is unduly crowded will step into the gutter to allow the stranger to pass.”

Women, too, the paper proclaimed, could pass through Little Syria unmolested, stopping at “queer little Syrian groceries and confectioners’ shops” to inspect sweetened, dried fruits and spices which might be served at a dinner, lending an air of exoticism to the proceedings.

Even in coffeehouses, if “an American woman elects to enter alone the men are particularly careful to avoid embarrassing her by staring, and when she is about to leave the door is opened for her with Chesterfieldian politeness.” Given the common assumption (occasionally correct, it must be said) that coffee-and-tea houses in SoHo and Chinatown were barely-disguised fronts for gambling and prostitution, the gallantry of Little Syria would have been an invitation to women who saw themselves as adventurers—here was a chance to mingle amongst the foreign, the strange, and return home with a story to tell and a dessert to shock one’s stodgier acquaintances.

Even through the lens of the privileged, there are signs of the diversity and creativity that fueled the Syrian Quarter’s day-to-day existence. Restaurant menus were reprinted in newspapers and rhapsodized over; not a single story about the place fails to describe baklava, leaving out not even the smallest detail:

“Made up of fifteen to twenty thin layers of paste, with butter in between, and in the centre of each walnut paste and ground sugar. The toothsome morsel then goes into the oven and is thoroughly baked.”

Peddling, of course (for what country does not send its citizens to American cities to sell goods on the street?), was a common occupation for Syrian men, but so too was importing and selling of “Oriental” goods, operation of bakeries and restaurants, and publication of newspapers—it was on Washington Street that the Linotype was adapted to produce Arabic type, with three newspapers to serve as many blocks and revolutionizing the transmission of information in the Middle East. Like the most celebrated men of the Gilded Age, the most respected members of the Syrian community in Lower Manhattan were those who threw themselves wholeheartedly into American capitalism. “This is a colony,” proclaimed the Times, “wherein nearly everyone is a merchant of his own account.”

* * *

Does the immigrant journey end at Ellis Island, or Castle Garden? Who among us hasn’t an elderly relative who can’t fathom the young person’s need to live in the cramped quarters of the city, surrounded on every side by other bodies? Little Syria (at least the prosperous part of it) began in the early 1920s to migrate across the Brooklyn Bridge, establishing itself along Atlantic Avenue in South Brooklyn. Manhattan’s Little Syria, though, was still a point of entry into the city for new immigrants, for those who shopped and worshiped there, and for those who, after coming thousands upon thousands of miles into a new world, saw Washington Street as home.

At last count, the population of Manhattan’s Chinatown neared 100,000 residents, and the neighborhood continues to expand northward, Mandarin and Cantonese lettering appearing on signs above storefronts on Broome and Rivington. Those streets, once the heart of the Jewish Lower East Side (in the early twentieth century, the Lower East Side, had it broken away from the rest of New York, would have been the largest Jewish city in the world), are still dotted with reminders of what once was—delis now attract tourists in search of iconic pastrami sandwiches, and discount garment shops still shutter on Friday evenings, leaving the goyishe to drink and make merry at bars and restaurants named for long-forgotten civic leaders.

Italians fled Mulberry Street en masse in the 1930s and 40s to claim their own pockets of suburbia in Bay Ridge and Bayonne (“The Italians,” my Calabrese grandfather once told me, “went off to fight in World War II and came back white.”). Still, though, the red, white and green banners adorn the lampposts, and bakeries still sell out of cannolis on Sunday afternoons (though really, they’re better on Staten Island).

Of Little Syria, there is nothing.

NYPLsepiaIn post-war New York, when anything was possible, Robert Moses envisioned five boroughs that could be traversed in less than an hour. What there were a way, he wondered, to begin in Lower Manhattan, pass underneath the East River, and spit out the cars everyone would surely acquire by decade’s end all the way in Brooklyn? After plans for a bridge fell through (in part because city officials felt such a structure would destroy Castle Garden, which, for Syrian immigrants arriving in New York prior to 1890, would have been the first American soil stepped upon), the city moved forward with plans for the Brooklyn-Battery tunnel.

The entrance to the Brooklyn-Battery (rechristened in 2010 as the Hugh L. Carey tunnel, though good luck finding anyone who’s ever used that name in a sentence) needed to be wide enough for both passenger cars and work equipment. Open space that could be paved and routed didn’t exist, and when Robert Moses needed something that didn’t exist? He made it.

The entrance to the Brooklyn-Battery (rechristened in 2010 as the Hugh L. Carey tunnel, though good luck finding anyone who’s ever used that name in a sentence) needed to be wide enough for both passenger cars and work equipment. Open space that could be paved and routed didn’t exist, and when Robert Moses needed something that didn’t exist? He made it.

On August 11, 1946, “Street of the Arabs” (again from the Times, though this time penned by a woman) declared,

“Washington Street, at the lower end of Manhattan Island, is today a condemned street. From Rector Street to Battery Place, all the people who live there and run restaurants and spice shops and Oriental bakeries and newspapers have received notice to vacate.”

Little Syria of the 1940s was still the social epicenter of New York’s Syrian and Lebanese communities, which by that decade had grown to nearly forty thousand. From all over Manhattan and Brooklyn, “Lebanese and Syrian Americans come down to the two small eating houses to enjoy sheesh kabab and stuffed grape leaves, and to talk politics, business, and home over the honey drippings of some real baklavah or the restful hubble of a water pipe.”

By the beginning of 1947, the Syrian Quarter would be gone. Three Washington Street buildings remain—a tenement, a settlement house, and a church (which most recently functioned as an Irish pub), and preservationists and stewards of Arab-American history are fighting to have the small collection of spaces designated as New York City Landmarks, offering the little (in that part of Lower Manhattan, anything under fifteen stories is practically Lilliputian) buildings some degree of protection from further indignities.

Syrian businesses continue to flourish in Brooklyn, in New Jersey, in Los Angeles. The breakup of ethnic enclaves is seen by many as a sign of progress, of assimilation. There is an ephemeral sadness, though, in the thorough erasure of Little Syria. Culturally, politically, sure—what might we see differently if this country halfway around the world existed at the base of our little island?

But there is also this:

“The old people like living on Washington Street. They feel at home there. They have everything they want and need right on the block—their friends, their church, their papers, their restaurants and their grocers, who go to great pains to import the spices they like for their food, and the special bakeshops that make the candy and pastry they have known and loved ever since they were children, back in Damascus and Beirut.”

Angela Serratore – Paris Review

A Moment in Ramallah / John Berger

Orientalism is a cultural and a political fact / Edward Said

Befriending Edward Said