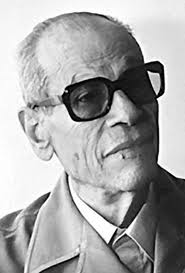

The Egyptian author and winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature Naguib Mahfouz wrote many great novels, among them Midaq Alley and Children of Gebelawi. But despite his greatness, did the “Pharaoh of Literature” perhaps hinder the development of the Arabic novel? Samir Grees has been finding out

Naguib Mahfouz, who went on to immortalize his hometown in numerous great works of literature and to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, was born in Cairo on 11 December 1911. This year, the Egyptian capital is commemorating the centenary of Mahfouz’s birth with a celebration of the writer and his literary legacy.

2011 has been declared Mahfouz Year. The programme of festivities was launched in Cairo in mid-December 2010 with an event that posed the following question: how is it possible to write novels in the shadow of such a literary giant? With all his literary achievements, is Mahfouz perhaps an obstacle for the development of the Arabic novel?

This question was first asked by the Egyptian critic Ragaa’ al-Naqqash at the end of the 1960s. At the time, the author of the Cairo Trilogy was so influential that the concern seemed perfectly justified.

Post-Mahfouz stagnation?

Mahfouz seemed to have found all the right forms for the modern Arabic novel. His work was highly esteemed by both readers and critics alike, and it is possible that this could have prevented other writers, especially younger ones, from breaking new ground. Al-Naqqash prophesied a period of stagnation in Arabic literature after Mahfouz, such as the ones that set in in England after Dickens, in France after Balzac, and in Russia after Dostoevsky.

However, the great master of Egyptian literature Edwar al-Charrat (b. 1926) holds a different opinion. Al-Charrat, whose novels have been translated into many languages including German, believes that “the development of the Arabic novel is not dependent on one person alone – regardless of the size of his cultural contribution”.

Yet according to the Lebanese poet and critic Abbas Beydoun, Mahfouz not only made a great contribution; he “was in fact the originator of the Arabic novel”. Beydoun adds that Mahfouz was “a novelist of international stature” who also exerted a great influence on the work of younger writers, and says that these writers owe him a great deal.

Literary rebellion against Mahfouz

This is also the view of the Jordanian writer Elias Farkouh. He comments that it was difficult, in the shadow of the great Mahfouz, to experiment with new forms of writing, and that it was only towards the end of the 1960s that young writers dared to “rebel against Mahfouz, in literary terms”.

One of these writers is Yusuf al-Qaid, one of the best-known writers of the Sixties generation. Although al-Qaid was very close to the much older Mahfouz and admired him greatly, he developed a different style of novel and represented a different political point of view. Furthermore, al-Qaid’s novels usually depict the lives of ordinary people in the Nile delta, whereas Mahfouz’s interest focussed solely on the middle classes of metropolitan Cairo.

“I didn’t let myself be influenced by him as a writer, but as a human being,” says al-Qaid, adding: “I was deeply impressed by his time management.” Mahfouz wrote most of his great works while still working as a civil servant.

Furthermore, Mahfouz suffered from an eye disease that meant he was only able to write for half the year. In autumn and winter, he had to be scrupulous about dividing his time between his writing and his work in the Ministry of Culture.

Openness to younger writers

Al-Qaid also points to other colleagues from the Sixties generation, such as Gamal al-Ghitani, Sonallah Ibrahim and Ibrahim Aslan, who all found their own literary paths independent of Mahfouz. In those days, Mahfouz would meet up every week with Al-Qaid and other young writers in Café Riche, in the centre of Cairo. Al-Qaid emphasizes that until 1994, Mahfouz followed the work of his younger colleagues with great interest.

That same year, a fanatic stabbed the then 83-year-old Nobel Prize winner in an attempt to assassinate him. The attack was prompted by the fact that many Islamists held Mahfouz’s novel Children of Gebelawi to be blasphemous.

The novel is a parable in which Mahfouz introduces characters reminiscent of God, Adam, Moses, Jesus and Muhammad. The novel was banned in Egypt for decades as a result, and was only published there in 2006 after it had already been translated into many other languages.

Remembering his Friday meetings with Mahfouz, Al-Qaid says: “Back then we would always give him our work to read. The following Friday he would give it back to us, and would give us his frank opinion.” Said al-Kafrawi, the short story writer, also went regularly to the meetings in Café Riche. “In winter we would only meet on Fridays, but in summer we met every day,” he recalls.

Al-Kafrawi remembers the warmth with which Mahfouz greeted him after he was released from prison. Mahfouz listened very attentively when al-Kafrawi talked about his time as a political prisoner under Gamal Abdel Nasser. In 1974, four years after Nasser’s death, Mahfouz published his novel Karnak Café, which deals with atrocities committed by the police state under Nasser. When Mahfouz saw the young storyteller again in Café Riche, he said to him: “Said, you are one of the characters in this novel.”

Mahfouz’s legacy today

Muntassir al-Qaffash, Mekkawy Said and Mansoura Ez Eldin are successful young novelists in Egypt who have won literary prizes and been translated into several European languages.

By the time they started writing in the 1990s, Mahfouz (whose Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded in 1988) was more of an icon than an obstacle. “Our generation,” says al-Qaffash, “had a high regard for Mahfouz’s literary achievements.” However, he and his colleagues felt challenged to “explore new territory”.

The 36-year-old Egyptian author Mansoura Ez Eldin agrees. However, she especially values Mahfouz’s love of experimentation; the fact that he was always trying out new forms. “The presence of a writer as great as Mahfouz is a stimulus for the further development of the Arabic novel, not the opposite,” she comments.

What remains?

The “Pharaoh of Literature” (Die Zeit) left behind an extensive oeuvre: 55 novels and collections of stories. Some of these have certainly dated a little, but many are still relevant today and are well worth reading. More than 20 of Naguib Mahfouz’s novels have now been translated into German, even more into English and French.

Some of his works are guaranteed to endure, according to the Moroccan poet and critic Hassan Najmi. He recommends that new readers should start with the works of Mahfouz’s so-called realistic period, such as Midaq Alley and the Cairo Trilogy (Palace Walk, Palace of Desire and Sugar Street).

Yusuf al-Qaid and Said al-Kafrawi, by contrast, particularly recommend Mahfouz’s later work: The Harafish, Echoes of an Autobiography, and The Dreams. “These novels take a covert look into the future,” says al-Kafrawi. “They are a personal coming-to-terms with life and death.”

Samir Grees

Translated from the German by Charlotte Collins

Samir Grees studied German Language and Literature in Cairo and gained a diploma in translation from the University of Mainz. He works as a freelance journalist and translator. Grees has translated numerous works of German literature into Arabic, including Ein liebender Mann [A Man In Love] by Martin Walser, The Pianist by Elfriede Jelinek, and Simple Stories by Ingo Schulze.

Qantara.de

A Moment in Ramallah / John Berger

Orientalism is a cultural and a political fact / Edward Said

Befriending Edward Said